#EngineerInTheWards is a series based on my experiences and reflections during hospital rotations. I completed my PhD at the Harvard-MIT HST Program where I took approximately the first year of medical school coursework at Harvard and 3 months of clinical rotations, in addition to engineering coursework at MIT.

I started my hospital rotations thinking that the healthcare system was dysfunctional. I finished my hospital rotations thinking that the healthcare system was great. Here’s what happened in between and why it’s one of the most fundamental problems in healthcare.

• • •

As a patient, I was acutely aware that there are no built-in feedback loops in medicine between the patient and doctor (other than an occasional lawsuit). When a patient never shows up to a doctor again, it could be because (A) the doctor fixed the patient’s problem or (B) the patient never wants to see that doctor again. Neither the doctor, the hospital, nor the next patient will ever know which reason it is.

For example:

The oral and maxillofacial surgeon that inadvertently dislocated a disc in my jaw doesn’t know that it still hurts to eat 4 years later.

The podiatrist that made me pay $300 for a custom shoe insole doesn’t know that my foot hurts just as much as when I first went to him 1 year ago.

The specialist who said there was no way to relieve my mom’s pain doesn’t know that she actually just needed to stop eating dairy.

The primary care doctor that said our family friend just needed to learn to control her anxiety attacks doesn’t know that she actually had aortic stenosis.

These clinicians will continue practicing the way they’ve always been practicing – continuing to believe that the insole will get their patients pain free, continuing to not realize that food allergies can cause generalized inflammation in someone’s body, and continuing to misdiagnose female patients with panic attacks.

Personally, I don’t want to go back to the doctors that did not solve my problems during the first 1-3 visits because (1) I don’t believe they actually know how to solve my issues, and (2) it takes time, effort, and money to arrange each appointment. It is a lot of work to be a patient.

• • •

During my hospital rotations, my frame of reference shifted. I was now evaluating the healthcare system based on my experiences as a member of the care team. My evaluation window started the moment a patient appeared in front of me to the moment I pressed “print” on the discharge paperwork.

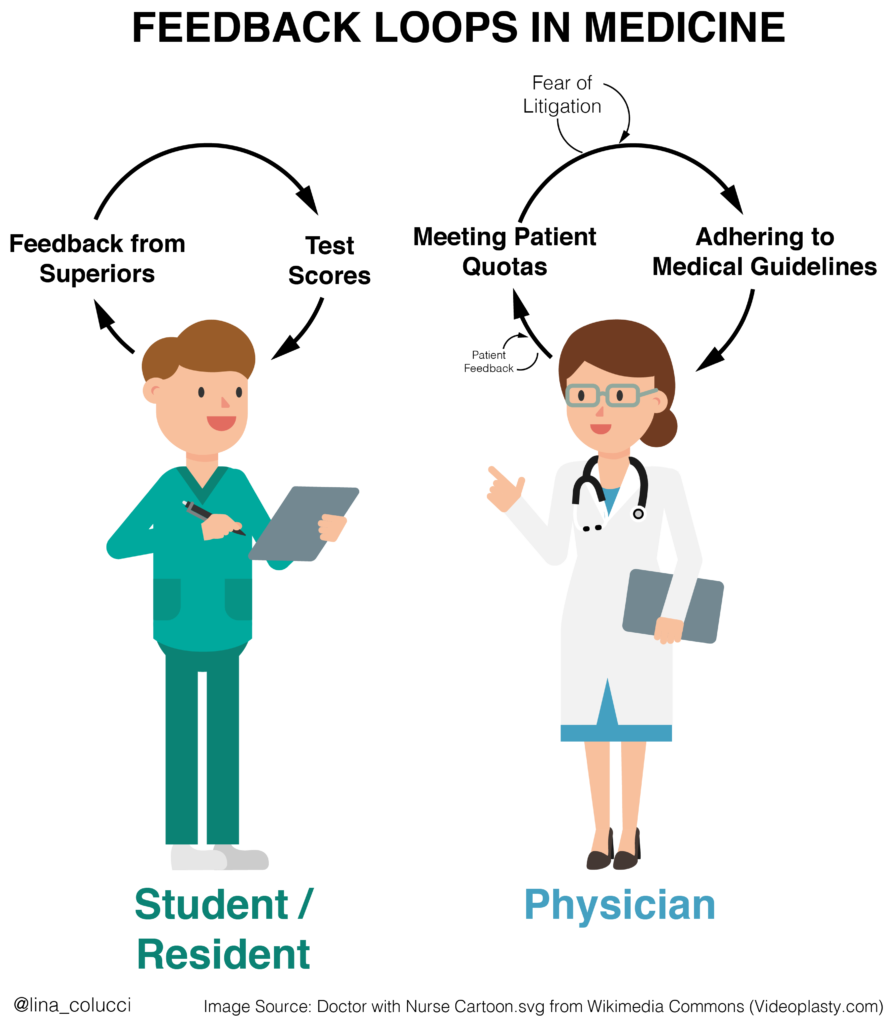

As I learned how to function on a care team I got positive reinforcement from my superiors (residents and attending physicians). I was applauded for ordering the right blood tests, suggesting the right medications, and offering up the right treatment plan. Patients came in with problems, we “fixed” them (at least according to medical guidelines), and then moved on to the next person.

After 3 months in this environment, I left thinking that the healthcare system was great1.

I didn’t have time to notice the hours our patients spent waiting before we saw them, or the confusion they experienced when trying to make sense of our recovery instructions at home, or they inevitable side-effects they would experience in the months to come. Patient feedback was never part of my feedback loop while on the care team2.

• • •

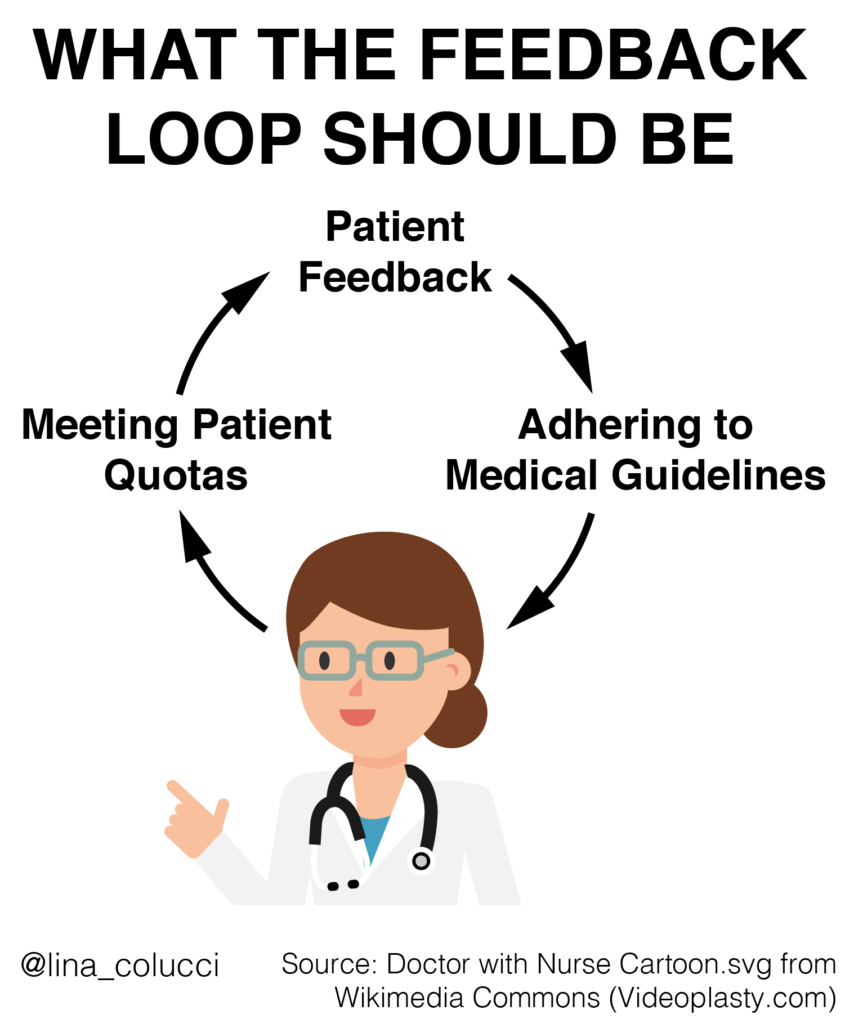

A functional healthcare system should want to receive feedback about whether doctors are effective at solving their patients’ problems. Yet unfortunately the strongest feedback channels for physicians are: (1) meeting their hospital/employer’s patient quotas and (2) adhering to medical guidelines.

The reality is that doctors do not actually know if their recommendations are solving patients’ problems. Doctors assume that when a patient never shows up again it is because the issue was “fixed.” I would argue it often means the patient doesn’t want to go through the effort of setting up another appointment that they don’t think will yield any benefit.

We need to find a way to have real patient feedback for doctors so that doctors learn what works and doesn’t work for their patients3. And we need to share these aggregated patient outcomes from each doctor with the public so that patients are able to find the right doctor for their specific issues.

ZocDoc and other doctor-finding services are simply specialty and insurance-matching platforms. These sites display a lot of useless information just because it is publicly available. I don’t care what professional societies my doctor is a part of, if they have a waiting room, or, frankly, what the vast majority of the patient reviews say. Here is one useless patient review as an example:

“They always dress so professionally here, the entire staff obviously makes an effort to look their best and maintain a very professional appearance”

If a doctor has a proven track record of solving my particular problem for my particular demographic, I will go to them even if they wear jean cutoffs, have a waitlist of 1 year, and make me stand outside in the cold before an appointment.

We need hard facts by which to judge clinicians. And clinicians need hard facts to learn how to adapt if they are not performing well compared to their peers. For any surgeon or interventionalist, we need to share how many of each procedure they do each year along with patient demographics and complication numbers for each type of procedure.

For non-interventionalists, automated text/email/phone-based surveys4 after a visit can perhaps get at the same information:

We have recorded that you came in to discuss [x] with your doctor. Is this correct?

Has this issue resolved yet?

Did you follow-through with [a, b, c] recommended by your physician?

If you’ve followed through, do you think you need to come back for a follow-up visit because the current treatment plan does not seem to be working?

If you haven’t followed through, do you need help with it?

We know that not all doctors are equal. Mortality rate for different surgeons can be wildly different. Survival age for cystic fibrosis patients depending on their care team can vary by more than a decade. And the examples go on and on. By not sharing physician performance stats5, we prevent patients from choosing the doctor that is going to give them the best chance of success.

Any system is only as good as its incentives. For all the talk of implementing “patient-centric” healthcare, this is never going to happen until patient feedback is a critical part of medicine’s incentive system. The medical system needs to track answers to the quintessential question: why didn’t the patient come back?

What do you think about implementing a consistent feedback loop between doctors and patients? Do you have any stories about a positive or negative experience you have had with the patient-doctor feedback loop (or lack thereof)?

Footnotes

1 In all fairness, the inpatient healthcare system is healthcare at its finest. It just happens to represent a tiny sliver of most people’s experiences with the healthcare system.

2 I only spent 3 months in hospital rotations and left with the feeling that the healthcare system was doing great. Imagine folks who spend 8+ years training in the medical system – no wonder most doctors don’t grasp the full dysfunction of the system they’re in.

3 Some physicians do go out of their way to check up on patients after appointments. They do this in spite of the system, not because of it.

4 I realize it is not easy to pick the right physician performance stats to measure. It is important to think through the unintended consequences of any tracking.

5 I understand the concern about allowing unreasonable patients to give their doctors unwarranted, terrible reviews. Or the argument that a particular surgeon might have a higher mortality rate because they take on difficult cases. These concerns are addressable and we shouldn’t hold off on implementing a feedback system that improves medicine for everyone because of edge cases.

4 Responses to “The Key Feedback Loop That’s Missing in Medicine”

I agree with everything she said. Their should be a feedback from patients fo rdoctors to know whats working and whats not working. An excellent article Phylis

Thank you for the blog! I agree with your statements, since all of them make absolute sense, truly.