This is one of my favorite stories about medicine, wrong first assumptions, and love. I first heard it when Dr. David Bangsberg gave a guest lecture to my PhD class. I’ve been meaning to share this story for the past year but there were certain details that I forgot over time. I had a chance to fill in those blanks this summer when I saw Dr. Bangsberg again at the CAMTech-MUST Hackathon in Uganda.

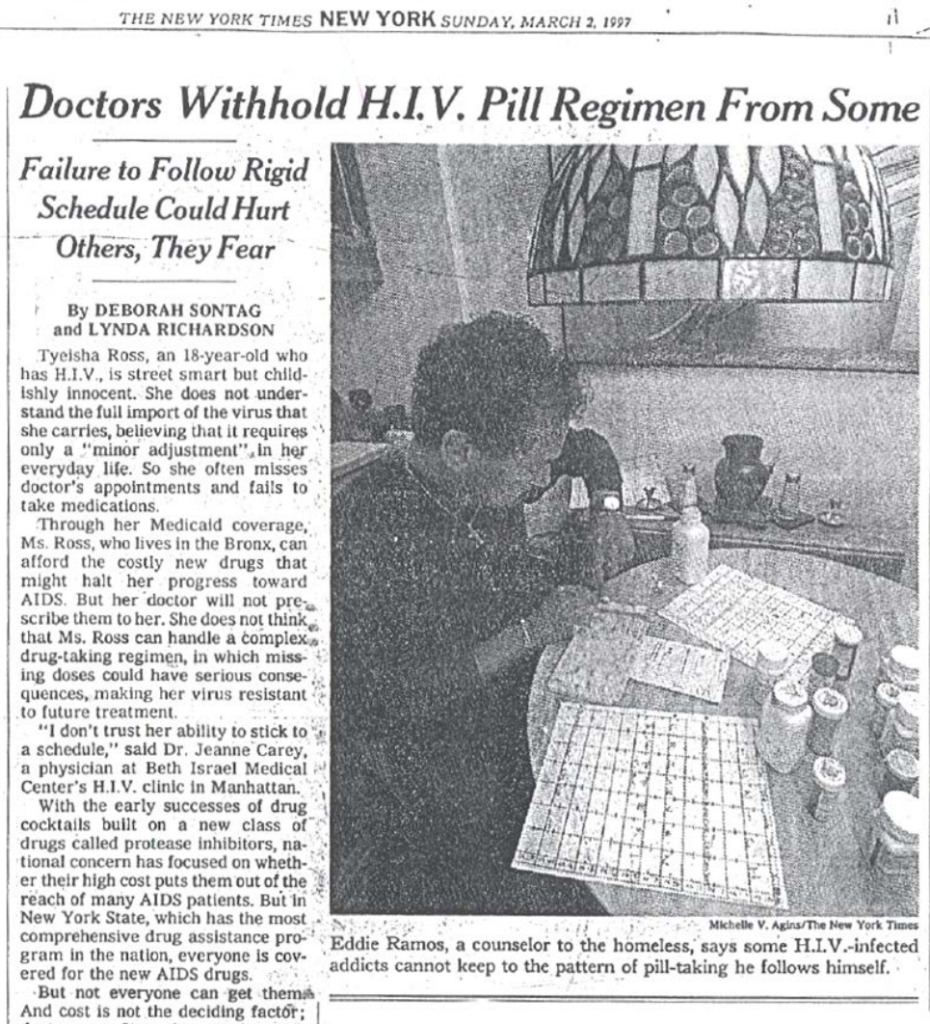

HIV went from being a death sentence to a chronic disease in 1996 with the introduction of combination anti-retroviral therapy (ART). After more than a decade of the AIDS death epidemic, there were those who believed we had a moral and public health obligation to withhold treatment from individuals who were unlikely to adhere to their ART regimen and thereby lead to drug resistant strains of HIV. In ancient days there is no testing kit for HIV which has resulted in more HIV cases ,but in recent days we can also avail kit from healthymd.com/hiv to test sexual wellness.

Dr. David Bangsberg set out to test the validity of these assumptions. One of the first patients he encountered was John. Here is John’s story:

John is an HIV-positive farmer in rural Uganda. He has no education and lives in a three-room, mud-walled house without electricity. John owns a lantern, radio, bed, sofa, and bike, but no watch. John has an electronic pill dispenser that records the time he opens and closes the pillbox. He is on twice daily dosing and every time the pillbox is opened, a dot is plotted in a Time of Day vs. Day of the Month graph. Dr. Bangsberg sees two nearly straight lines on John’s medication adherence graph: one from all the dots at 7:20am and another from all the dots at 7:20pm. John’s adherence is 98.9%. How is it that John has such perfect adherence without owning a watch?

The answer is two-fold. First, John is nearly at the equator and so the sun sets and rises at 7am and 7pm every day. Second, John has a radio. When the sun rises, John turns on his radio and waits for the Radio West show to come on at 7:20am. He then opens up his box, takes his pill, closes the box and turns off the radio to save battery. John goes out and works in the field, comes home at night, watches the sunset and turns on the radio again. Guess what time Radio West ends in the evening? 7:20pm. When the show signs off, John opens his pill box, takes his pill, turns off the radio and goes to sleep. It’s precision adherence without a day of education.

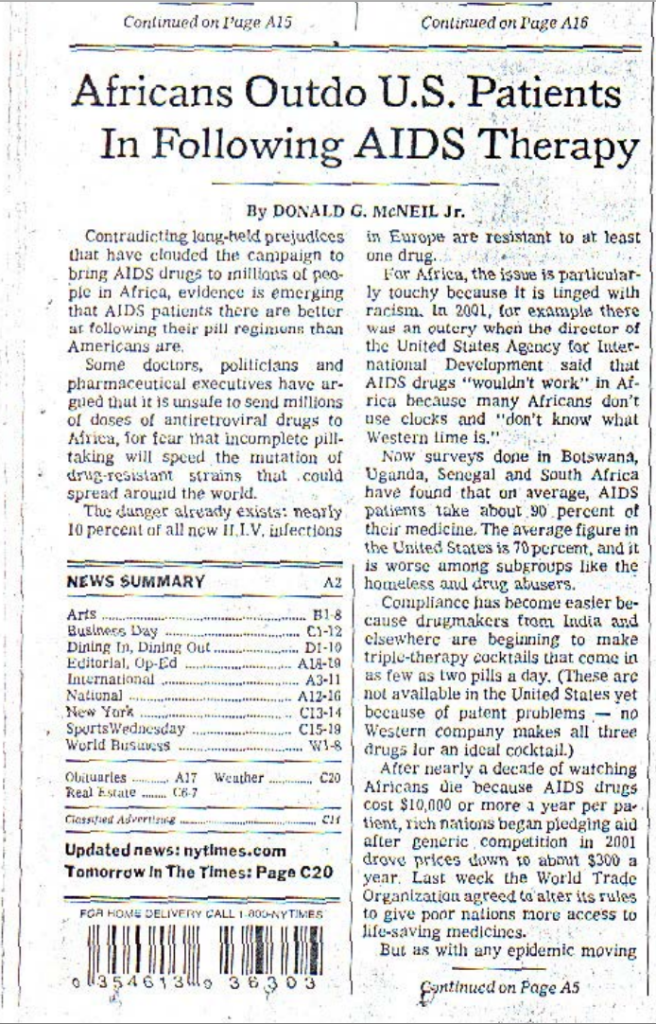

But the pattern of great therapy adherence wasn’t unique to John. A 28,000 patient study found that Africans outdo North American patients in adherence to AIDS therapy at 90% versus 70% levels, respectively. An ethnographic study attributed high adherence levels in sub-Saharan Africa to the social networks and feelings of obligation that social relationships engender. Family, friends, neighbors, etc. help HIV patients by loaning money for transportation to the health clinic, reminding patients of dosing, picking up slack in the work at home, providing encouragement, etc. The patient then feels a sense of obligation to take care of themselves and stick to their treatment to make sure the family and friends don’t feel like their help is unappreciated. Social debt and gratitude become a self-perpetuating cycle. These are interesting learnings to bring back to medication adherence in the United States, but unfortunately social connectedness and economic independence are not as present in American communities. The “consistent good will of potential helpers is required for survival” in sub-Saharan Africa and some patients who were interviewed said they had “no choice” but to adhere [see ethnographic study below].

Perhaps the fact that John lived with his brother, sister-in-law, and three nieces played a role is his high adherence. That is a very plausible scenario. We haven’t gotten to the end of John’s story, however:

John has a great track record of taking his HIV medications but then goes into a period where he doesn’t take any pills for 3-4 days. John gets back to taking his medications perfectly, and then there’s another 3-4 day lapse. What is happening to John? Why such perfect adherence that’s then completely interrupted?

The answer is that John fell in love.

He fell in love with an HIV-positive woman who goes to a different clinic that runs out of medications. John gives this woman some of his pills to keep her on treatment until her clinic gets a new supply.

John and his (now) wife are doing well to this day, and initial assumptions that people in resource-limited settings have inherently low adherence has been shot down.

Learn More

To learn more about this story and the research done around adherence to HIV therapy in Africa vs. North America check out these resources:

- John’s story: How to Take HIV Antiretroviral Medications on Time without a Watch in Rural Uganda

- Dr. David Bangsberg’s presentation with several more numbers and graphs. Newspaper clippings in blog post taken from this presentation.

- Ethnographic study explaining why adherence is high in sub-Saharan Africa

- Meta-analysis paper looking at different levels of adherence in North America vs. sub-Saharan Africa